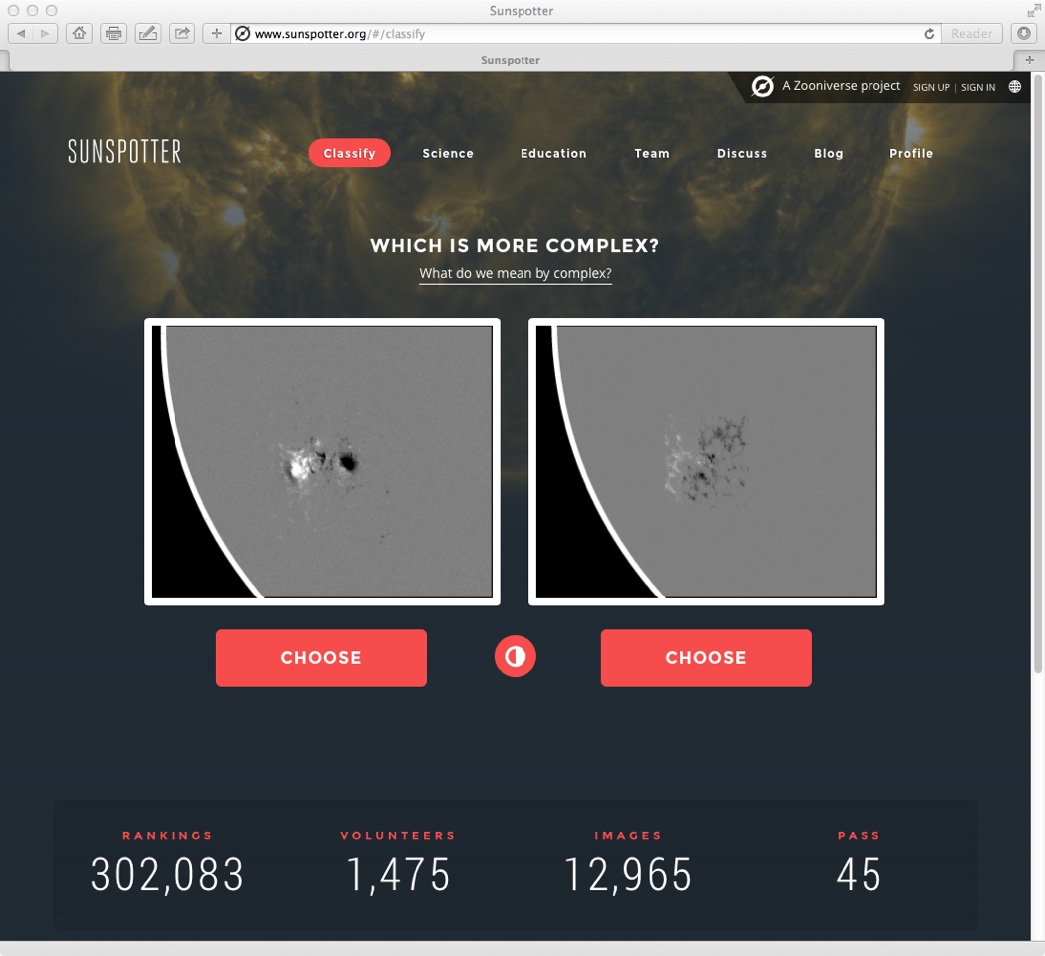

This summer, we conducted four pilot workshops introducing kids to space weather forecasting and classifying magnetograms. We used Sunspotter, the Zooniverse citizen science project developed by FLARECAST’s Irish project partners.

Sunspotter is a platform for crowdsourcing magnetogram classification to a large number of eyes and minds. It is a great tool for involving people without a background in science. And it fits particularly well with FLARECAST outreach.

Should you consider using Sunspotter for your outreach activities, please find below an outline of one of the many ways to do it. It describes a three hours workshop for which 10 to 13 years old children registered in advance. The materials we used can be found in the Workshops section of this website.

SETTING THE CONTEXT: SPACE WEATHER

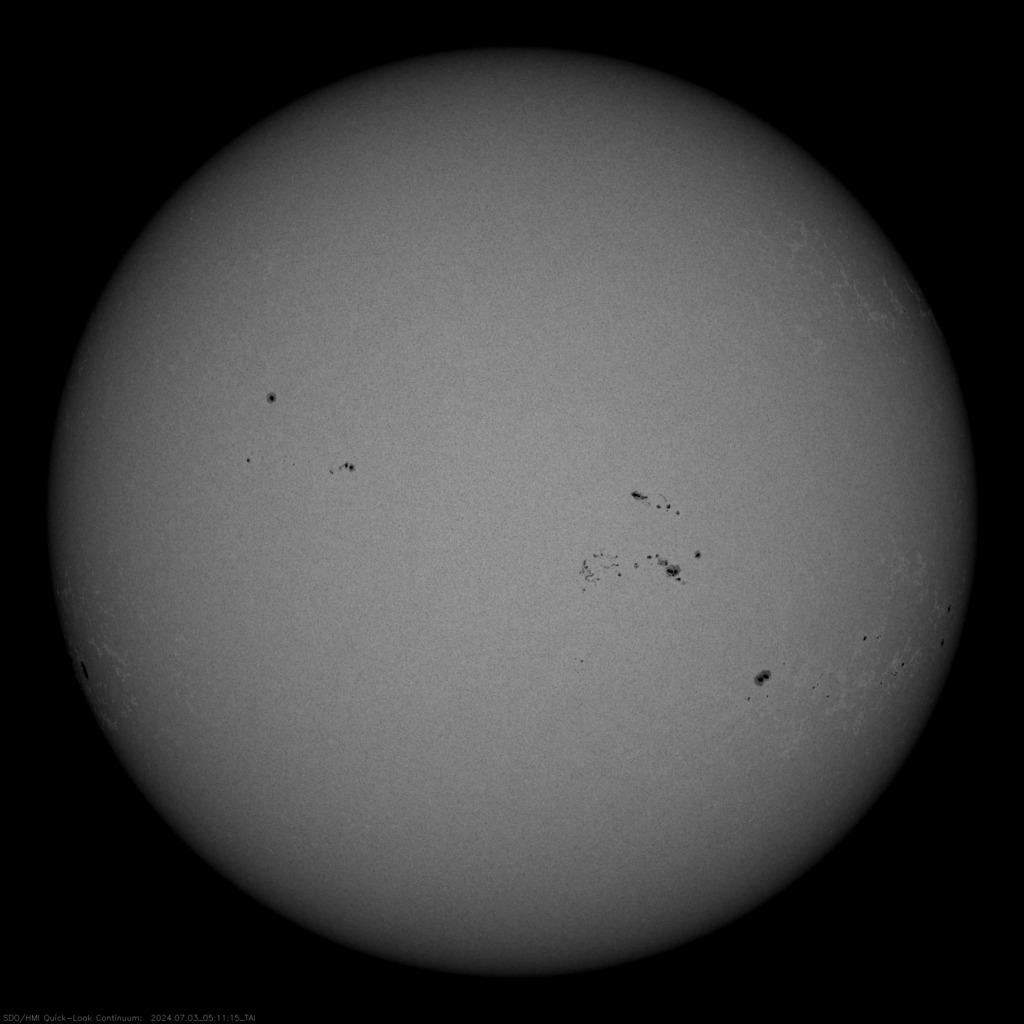

After some getting-to-know-each-others activities, André and Marco introduced the kids to ground- and space based observation of the sun, space weather forecasting and big data by a simple power point presentation with a lot of scope for questions and discussions.

GETTING MORE SPECIFIC: FLARES AND MAGNETIC FIELDS

We got into more details (very shortly) explaining flares as explosions resulting from particular processes around sunspots on the solar surface. Playing with magnets and framed iron filings, although on a small scale, kids got a feeling of the invisible magnetic force.

We showed them how magnetic fields are made visible in magnetograms and had them practice observation skills matching magnetograms to AIA 171 UV-images.

Next, they learned to identify magnetic configurations likely to produce a flare. Finally, they received a mini-training in flare forecasting, assessing magnetograms for configurations likely to explode or not.

CONTRIBUTING TO SCIENCE: CLASSIFYING MAGNETOGRAMS

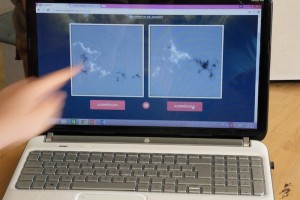

Now, they were ready to go. The newly baked citizen scientists analysed magnetograms on the Sunspotter online platform. Although the activity is technically easy to carry out – compare two images, assess complexity, click -, it is not always easy to decide which sunspot group is more complex. Participants did the activity in groups of two or three, discussing every image in order to achieve quality work rather than just keeping on clicking. We asked them to safe particularly interesting or funny looking magnetograms for keeping them more focused.

The kids classified magnetograms until they got bored. This took between 15 and 45 minutes. After, they made their own iron filing magnetic field frames to take home, share with family and friends and remember the workshop over a longer period of time.

OUTCOME

Initially, workshop participants didn’t believe that they would be able to contribute to real science. After the introduction, they understood why their contribution was needed. This was highly motivating and made them proud.

The extensive introduction helped participants understand the images they classified and make sense of the activity. This probably contributed to the comparably long attention span.

All in all, a few dozens kids classified a few thousands of images in our workshops. In numbers of classifications, this is not much. However, I think that, by the help of Sunspotter, we were able to provide some quality engagement time with FLARECAST scientists with a topic they were highly interested in.

Although we encouraged participants to continue classifying magnetograms or try another Zooniverse citizen science project at home, there is no evidence that they did so. For me, the question of how to get kids (and adults) in Switzerland (and in other countries?) to be part of the global citizen science community is still open. Strategies in fostering a culture of science participation over a longer period of time are needed.

FLARECAST outreach on SlideShare

FLARECAST outreach on SlideShare